Lean manufacturing had to start somewhere. While there is no set date or time for when Lean became Lean, Eli Whitney was certainly a key figure that helped develop components of the well-known method. Eventually, his contributions made Lean into what we know today as continuous improvement, waste reduction, increased efficiency, and improved production methods.

Everyone knows about the invention of the cotton gin, but are they familiar with Whitney’s work in popularizing interchangeable parts and mass production? Stick with us and learn all about this inventor and his contributions to modern manufacturing practices.

Who was Eli Whitney?

Born December 8th, 1765, in Westborough, Massachusetts, Eli Whitney Jr. is remembered as an influential American inventor. In fact, most people recognize him as the inventor of the cotton gin, a machine that revolutionized the process of harvesting cotton.

Whitney Jr. was the son of Eli Whitney Sr. and Elizabeth Fay. Even though he grew up on the family’s farm, Eli had no interest in following in his family’s footsteps. Rather, he was interested in machinery and new technology. His affinity for engineering and invention began at a very young age. In fact, by fourteen he was already manufacturing nails during the revolutionary war in his father’s workshop.

Unfortunately, Eli’s mother died when he was eleven. Once he came of age to go to college, his stepmother opposed, leaving him to save his own money by being a farm laborer and teacher for the time being.

After graduating in 1792, Whitney was expecting to study law after graduating from Yale but fell short on funding, leading him to accept an offer in South Carolina as a private tutor. However, he never made it to his destination. On his way to South Carolina, he met Mrs. Catherine Littlefield Greene, the widow of war hero Nathaniel Greene. She convinced Whitney to accompany her and her soon-to-be husband to their plantation in Georgia called Mulberry Grove. Her husband Phineas Miller eventually ended up being Whitney’s long-time business partner.

This is what would begin his engineering career, as Mulberry Grove is where he learned all about the production of cotton.

The Creation of the Cotton Gin

When Whitney reached Mulberry Grove in Georgia, he had the chance to learn all about the process of growing and processing cotton. At the time, cotton was not as profitable as it could be because of how difficult it was to clean. That was also at the time tobacco profits were shrinking due to high supply and not enough demand, as well as the problem of soil exhaustion. Cotton was supposed to revitalize the South’s economy, and it did with Whitney’s clever invention.

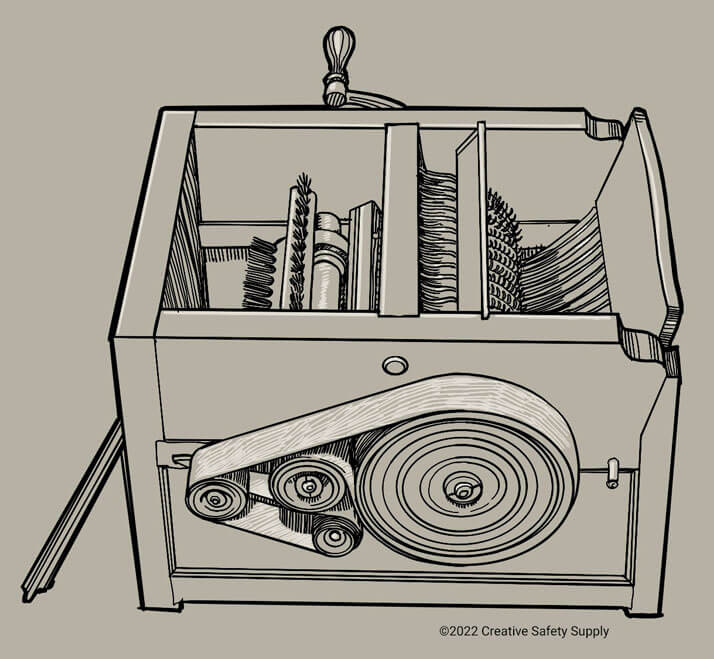

When faced with Greene and Miller’s problem regarding cotton production, Whitney jumped into action and built a prototype of the cotton gin in only a few weeks. The machine was made up of a hand crank attached to a rotating wooden drum with small hooks that grabbed the raw cotton fibers and pulled them through a mesh. A mesh that was too small for the cotton seeds to make it through.

The cotton gin, short for cotton engine, was an incredible turning point for southern cotton farmers. This is because short staple cotton, the only variety of cotton that could be grown inland in the south, was difficult to process in that picking out the seeds by hand was time consuming. This drove the profitability of cotton down at the time because of that arduous cleaning process.

While the cotton gin was a godsend for these people’s livelihoods, it also unfortunately worked to perpetuate slavery in the South for another 70 years. The cotton gin could clean up to 55-60 pounds of cotton in a single day whereas only one person could clean about a pound a day. With a higher volume able to be cleaned with the help of the cotton gin, that gave plantation owners a chance to plant more cotton, which meant they needed more people to work in the fields. Unfortunately, the simple solution for them at the time was to just purchase more slaves.

A Successful Invention, But Not Profitable

Whitney applied for a patent on his cotton gin in 1793 and received it in 1794. Success! Now they were on their way to becoming rich along with the farmers who will be able to sell more of the versatile textile material, so they thought.

In the beginning, both Whitney and Miller wanted to charge farmers to clean their cotton for them. The price they came up with was 2/5ths of the total profit from the cleaned and sold cotton. However, no farmers wanted to relinquish that amount. Instead, the farmers wanted the machine to own, a one-time cost that would increase their yield of sellable cotton for years thereafter.

Unfortunately, Whitney and Miller could not build enough cotton gins to sell as the alternate option. This is where it began to go downhill. Other inventors began to make their own cotton gins and farmers began to also make their own versions; some even improved upon the original idea. At the time, patent infringement was rampant because the laws simply were too young and inexperienced with protecting intellectual property.

Eventually, the cost of protecting their rights to the cotton gin patent is what drove them out of business in 1797. Whitney never profited from his invention. Yet, it became an essential part of the Southern American way of life and economy. Not to mention the fact that the cotton gin enabled cotton exports to grow from less than 500,000 pounds in 1793 to around 93 million pounds by 1810. From 1820 to1860 cotton made up 50% of U.S. exports overseas.

Whitney’s Contribution to Lean Manufacturing

We know Lean had to get started somewhere, and Whitney’s contributions were definitely part of those beginnings. However, let’s first talk about what Lean manufacturing is today, starting with the basic five Lean principles.

- Identify Value – Value is what the customer wants and what they believe is valuable in a product they want to purchase. This means the time it takes to produce the product, how long it will take to be delivered to them, how expensive it is, and anything else that is important to the consumer.

- Map the Value Stream – Once the team has decided what the end product will look like and how the product will get there, they must map the value stream. This is essentially a drawn map that includes the origins of raw product from suppliers all the way to the distributor, and transportation involved in getting the product delivered to the customer. This can involve either an individual or a store. Once this map is made, points that do not provide value can then be identified and eliminated for being wasteful.

- Create Flow – Once the waste has been eliminated, then the team must still make sure no bottlenecks or holdups can occur within the new, and ideally improved, process.

- Establish Pull – Now is the time to master just-in-time production and essentially have only enough product to meet demand. When performed correctly this action can help eliminate waste such as excess product and the need to store that product.

- Seek Perfection – There is always improvement to be had in manufacturing processes. Because of that, this is often the most important step out of all five Lean principles!

The main idea behind Lean manufacturing is to create the highest value possible with the least amount of waste. The use of the cotton gin is a great example of this because the value of cotton went up since the process eliminated the original arduous process of cleaning cotton. As a result, the improved process paved the way for increasing production, not only giving the American South the chance to export more product overseas, but also the ability to bring in more revenue.

Did you think Whitney’s most notable invention, the cotton gin, was what elevated him to the status as a Lean founder? It’s not! his real accomplishments came in the form of contributing to mass production fundamentals as well as popularizing interchangeable parts.

Experimentation in Mass Production

By the time Whitney’s business involving the cotton gin fell through in 1779, he gained a reputation for being innovative and won a contract from the government to deliver a massive number of muskets in only two years.

10,000 muskets to be exact.

This was unheard of at the time as muskets were made individually by gunsmiths, craftsmen that essentially made each gun by hand, often with unique parts. At the time, gunsmiths only produced about 300 hundred guns per year. What did Whitney do first to achieve this? He built a town of course!

Whitneyville, came into existence in 1798 when Eli Whitney bought land intending to build an arms business, The Whitney Armory. On that land he built the arms factory along the Mill River as well as housing for those that would work in the factory and their families.

After all this to-do, Whitney didn’t complete all 10,000 muskets until 1809! Well past the contract’s two-year agreement. However, his contribution to the idea of mass production certainly wasn’t underappreciated. In fact, his method of mass production went hand in hand with the concept of interchangeable parts.

The Rise of Interchangeable Parts

Even though Whitney never met his goal of 10,000 muskets in two years, he did make some considerable contributions in terms of popularizing interchangeable parts. It’s specifically noted that he popularized the idea, Eli Whitney certainly didn’t come up with the idea as it has been traced back all the way to the Punic Wars fought between the Roman Republic and Ancient Carthage, and perhaps even before then.

The ability to make repairs on the field of battle, theoretically, would have been incredibly useful. This is because most artillery at the time was made in such a unique manner that repairs had to be made by a skilled gunsmith. Interchangeability, especially at the time of the French Revolution that incited conflict between America, France, and Britain, was hastily adopted. Or at least attempted.

Though Whitney showed that it was feasible, he couldn’t quickly manufacture those arms that were mentioned earlier. In short, they were all good ideas, but America needed more time in terms of developing a standardized system for interchangeable parts.

Conclusion

Eli Whitney was certainly an incredible inventor at the time who contributed to some of the standard Lean practices that our safety professionals practice every day in modern America. However, Whitney ran into many inhibiting factors in terms of the success of his inventions, leading him to see virtually no profit from any of them.

Similar Articles

- Henry Ford and Development of Assembly Lines

- The Development of Scientific Management by Frederick Taylor

- Lean Manufacturing [Techniques, Solutions & Free Guide]

- Quality Control in Manufacturing

- Frank and Lillian Gilbreth: Standardization, Ergonomics, and Lean Manufacturing

- Kaizen and Lean Manufacturing

- Toyota Production System (TPS & Lean Manufacturing)

- The Origins of TPS

- 5 Lean Principles for Process Improvement

- Autonomous Maintenance: The Key to a Healthy TPM Program