Standardization is the name of the game when it comes to efficiency. However, unlike the strict time studies performed by Frederick Taylor, there was an opposing argument for the optimization of movement instead. Optimizing movement was more focused on reducing fatigue, allowing them to complete more in terms of quantity without doing more strenuous activity.

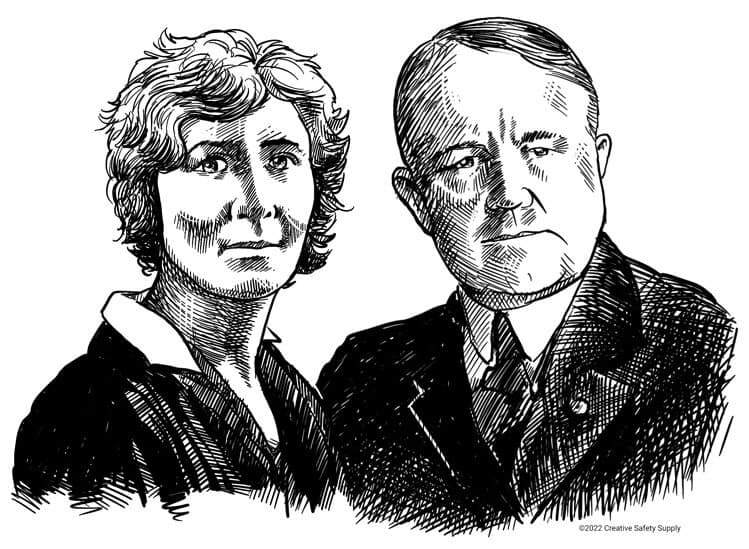

The two that lead this new industrial management technique were Frank and Lillian Gilbreth. This husband-and-wife team revolutionized the way people worked in both industrial environments and within the household. The Gilbreths were two of the world’s greatest industrial management engineers of their time.

Who was Lillian Moller Gilbreth?

Lillian Moller Gilbreth was born on May 24th, 1878, in Oakland, California. She was the oldest of nine children born to Annie and William Moller. Lillian was incredibly successful in primary school but had to convince her father to attend college once she came of age. She succeeded and began her freshman year at the University of California.

Moller graduated in 1900 with a bachelor’s degree in modern languages and philosophy and then received her Master’s in literature in 1902. Her goal was to eventually become a teacher, so much so that she had taken enough education classes to receive a teaching certificate.

In 1903, Moller began her Ph.D. program at the University of California. Though, shortly after, in the spring of 1903, she went off to explore Europe. On her way there when she stopped in Boston, Moller met her chaperone’s cousin, Frank Gilbreth. They ended up marrying in October of 1904 back in Oakland, California and relocating to New York on the opposite side of the country.

She completed her dissertation for a doctorate at the University of California in 1911, but due to her non-compliance with residency requirements, she did not receive her Ph.D. However, Moller persevered. They relocated their family to Providence, Rhode Island where she enrolled at Brown University and earned her Ph.D. in applied psychology in 1915.

Moller was an astounding woman. She was the mother of 12 children, an educator, a consultant, on top of that, Moller was considered to be the first industrial/organizational psychologist and the first woman engineer to earn a Ph.D.

Who was Frank Bunker Gilbreth?

Frank Bunker Gilbreth was born on July 7th, 1868, in Fairfield, Maine. He was the youngest child of three born to John and Martha Gilbreth. Unfortunately, Gilbreth’s father died suddenly from pneumonia when he was very young. This incited two moves to and within Massachusetts to try and make ends meet.

Unlike his future wife, Gilbreth wasn’t much of a great student in his early years until he attended high school where math and science classes began to interest him. However, when he was accepted to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology he declined to work instead. His goal was to try and help his mother quit the boarding house she opened to support her family.

Frank began his journey in industrial management by becoming a bricklayer’s assistant. In this position, he began to contrive the “one best way” in all aspects of his work. Because of this, he was able to ascend the ranks from assistant bricklayer to chief superintendent after only ten years. He was 27 at the time. Although, he left his job at Whidden Construction Company soon after since they refused to make him a partner of the business.

After Gilbreth left, he founded his own contracting firm in 1895 where he and his team worked on over 90 large-scale projects ranging from:

- Factories

- Paper mills

- Canals

- Powerhouses

- Dams

Nine years later he married his wife and they both became a powerful team in terms of the scientific development of early Lean manufacturing techniques.

By the time 1912 rolled around, Gilbreth’s construction companies closed, and he transitioned into a new field of work referred to as efficiency and management engineering. Something he had begun to experiment with when he first started as a bricklayer. During this time of his life, both he and Lillian collaborated on these theories to the point where they were experimenting with motion studies in their own homes. In fact, their children were also participants in their efficiency studies.

Unfortunately, Frank died by heart attack at the age of 55 in 1924, Lillian never remarried and outlived him by 48 years. However, after his death, Lillian persevered and ran their consulting business Gilbreth, Incorporated by herself for decades after he died. She herself became known as “America’s first lady of engineering.”

The Gilbreths’ Contribution to Modern Lean Manufacturing

One of the eight wastes of Lean includes excess motion. The unnecessary movement by people can be detrimental to workplace productivity. Not only that, but excess movement often leads to fatigue, and we all know fatigue is the precursor to human error. Human error equates to a loss in productivity because of the inevitable decrease in quality product as well as factory delays and shutdowns. This snowball effect can be one of the largest threats to a successful business. If only “the one right way” of performing a task could be standardized. Well, that’s what Frank and Lillian Gilbreth developed!

The Gilbreths devised their management theory in terms of motion by combining both Lillian’s expertise in psychology and Frank’s expertise in the construction world. Together, they collaborated on developing terminology to scientifically determine the one best way for employees of all ages and professions to complete their jobs in a way that benefitted both the employee themselves and the company.

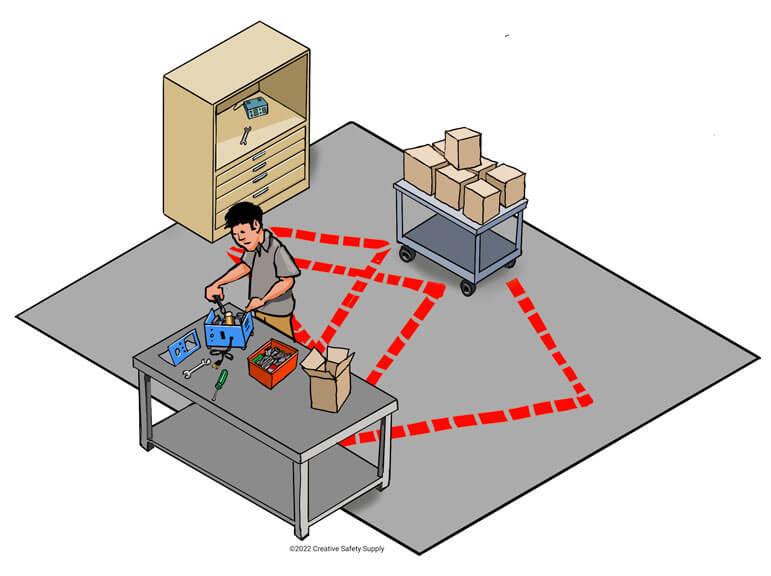

How did they do this you ask? The simplified version is as follows; the pair first began with using motion picture cameras to record the workers performing a task. Then they would observe the actions that the employee performed and apply any of the eighteen behavioral units they called Therbligs to each step of the process. Then they were able to not only find a faster way of performing a task, but they were able to simplify it in a way that reduced worker fatigue. Or at least, that was the goal.

In short, the Gilbreths developed what we know today as ergonomics! Standardization, ergonomics, worker productivity, all of these play an important part in Lean manufacturing. In fact, let’s go over the five principles of Lean manufacturing:

- Define Value – What does the customer need and want? This can refer to the turnaround time in terms of delivery and manufacturing speed, the price point, etc.

- Map the Value Stream – Draw out a map that shows the entire process from obtaining the raw materials to the finished product. It can focus on any aspect of manufacturing such as design, production, admin, and even delivery. With everything written down, you can then determine wasteful practices and eliminate them.

- Create Flow – After all the wasteful practices have been eliminated, you can then begin to make sure production flows smoothly from one step to the next. This is the time to look for interruptions, delays, or even bottlenecks that inhibit efficiency.

- Use a Pull System – Improved flow equates to improved time to market, which in turn helps facilities create just enough product to keep up with demand. This is known as Just-in-Time manufacturing.

- Pursue Perfection – Lean manufacturing techniques must be accepted by the whole team to work! With that being said, seeking continuous improvement and standardization is essential for the company culture to embrace, it will give them the drive to maintain the established standards of Lean manufacturing.

Do you notice how the Gilbreths’ motion studies have impacted modern Lean manufacturing principles? Their foundations for efficiency can be seen making an impact in each of the existing five Lean manufacturing principles, especially in the step of mapping the value stream. However, they began with motion picture observations rather than notating the steps on a map.

The Concept of Ergonomics

Lillian and Frank Gilbreth were two of the first people to work on ergonomic activity in the workplace. Ergonomics is the act of applying both psychological and physiological principles to the design of products, processes, and systems in an attempt to reduce human error as well as improve the safety and comfort of the operator or worker. In short, ergonomics makes for happier and healthier employees!

Take for example office workers and management. Ergonomics always seems to the top thing to optimize in cubicles where employees spend all their time during the day. Whether it be concerning their chairs, keyboards, and even computer screens. However, ergonomics extends into manufacturing as well to prevent serious or lasting injury while people perform repetitive tasks such as lifting, bending, and twisting.

Two studies published by Frank and Lillian include one titled Fatigue Study in 1916 and another titled Applied Motion Study in 1917. While these are only two of their many publications, they are two of the most notable. These papers established the need for more ergonomic working conditions for employees to reduce fatigue and be more successful at performing their tasks. Lillian’s ergonomics emphasized the need for better lighting to reduce eye strain, better fitting chairs to reduce pain, and coffee breaks!

Aside from the working world, and after Frank’s death, Lillian continued her work with motion studies by working to improve home ergonomics, particularly with wives in mind. In fact, she’s the one who came up with modern kitchen efficiency.

What are Therbligs?

A Therblig describes 18 different elemental motions that workers use every day. The word Therblig is quite clever as it is Gilbreth spelled backwards with the ‘th’ transposed.

These movements are integral to Frank and Lillian Gilbreth’s Motion Studies. They are as follows:

- Reach – Receiving an object with an empty hand.

- Grasp – Grasping an object with the active hand.

- Transport Loaded – Moving an object using a hand motion.

- Hold – Holding an object.

- Release Load – Releasing control of an object.

- Preposition – Positioning and/or orienting an object for the next operation and relative to an approximation location.

- Position – Positioning and/or orienting an object in the defined location.

- Use – Manipulating a tool in the intended way during the course working.

- Assemble – Joining two parts together.

- Disassemble – Separating multiple components that were joined.

- Search – Attempting to find an object using the eyes and hands.

- Select – Choosing among several objects in a group.

- Plan – Deciding on a course of action.

- Inspect – Determining the quality or the characteristics of an object using the eyes and/or other senses.

- Unavoidable Delay – Waiting due to factors beyond the worker's control and included in the work cycle.

- Avoidable Delay – Waiting within the worker's control which causes idleness that is not included in the regular work cycle.

- Rest – Resting to overcome a fatigue, consisting of a pause in the motions of the hands and/or body during the work cycles or between them.

- Find – A momentary mental reaction at the end of the Search cycle. Seldom used.

Each action was assigned a Therblig, or standardized activity as it is also called. Anything else that was taking place was either condensed or eliminated if possible. Therefore, creating a more efficient procedure.

Time Studies vs. Motion Studies

It’s a common misconception that the Gilbreths’ work is associated with Frederick Taylor’s. However, Time and Motion studies, while the name is combined, go about workplace efficiency in completely different manners. Let’s start by quickly going over Taylor’s principles of Scientific Management.

Taylor’s four principles included:

- Replacing any rule-of-thumb work methods with those that were based on a scientific study of the unique task.

- Scientifically select, train, and develop each employee instead of leaving them to train themselves.

- Provide both detailed instruction and supervision for each worker’s task.

- Divide work nearly equally between managers and workers. Managers are to apply scientific management principles to planning work and the workers are to perform the planned tasks.

Taylor was entirely focused on reducing processing time in manufacturing facilities. Due to equating worker to machines, the morale was often low in workplaces where Scientific Management was implemented.

Frank and Lillian Gilbreth took a different path through their own Motion Studies concept. As mentioned earlier in this article, Motion studies were used to develop a “one best way” for completing a task. That “one best way” method of improvement considered the human aspects of manufacturing. The Gilbreths were concerned for the welfare of the workers and prioritized efficiency over profit.

In a way, the Gilbreths took Scientific Management and improved it for the benefit of workers. A more efficient process that also made for happier employees.

Similar Articles

- The Development of Scientific Management by Frederick Taylor

- Ergonomics and Workplace – Everything You Need to Know

- Eli Whitney: A Key Player in the Development of Early Lean Manufacturing

- Kaizen and Lean Manufacturing

- A Look at Training Within Industry (TWI)

- Lean Manufacturing [Techniques, Solutions & Free Guide]

- James Womack and the Creation of the Lean Enterprise Institute

- Toyota Production System (TPS & Lean Manufacturing)

- 5 Lean Principles for Process Improvement

- Henry Ford and Development of Assembly Lines